Business

From the Archives: Hash in the U.S.S.R. (1974)

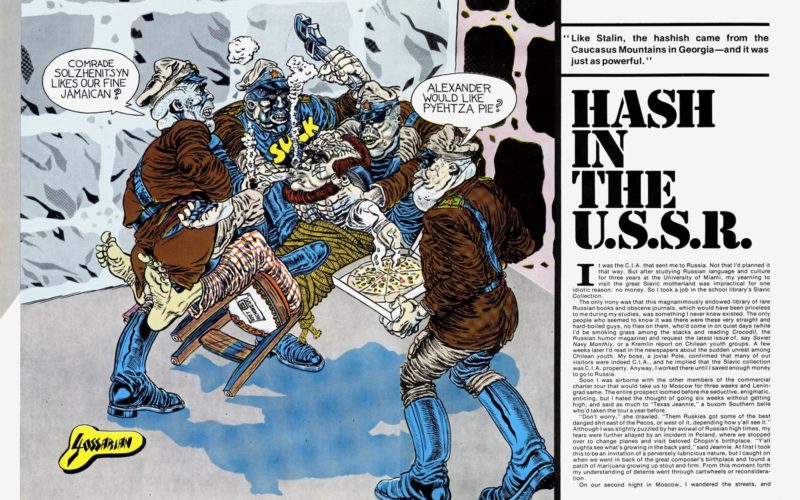

“Like Stalin, the hashish came from the Caucasus Mountains in Georgia—and it was just as powerful.”

It was the C.I.A. that sent me to Russia. Not that I’d planned it that way. But after studying Russian language and culture for three years at the University of Miami, my yearning to visit the great Slavic motherland was impractical for one idiotic reason: no money. So I took a job in the school library’s Slavic Collection.

The only irony was that this magnanimously endowed library of rare Russian books and obscene journals, which would have been priceless to me during my studies, was something I never knew existed. The only people who seemed to know it was there were these very straight and hard-boiled guys, no flies on them, who’d come in on quiet days (while I’d be smoking grass among the stacks and reading Crocodil, the Russian humor magazine) and request the latest issue of, say Soviet Navy Monthly, or a Kremlin report on Chilean youth groups. A few weeks later I’d read in the newspapers about the sudden unrest among Chilean youth. My boss, a jovial Pole, confirmed that many of our visitors were indeed C.I.A., and he implied that the Slavic collection was C.I.A. property. Anyway, I worked there until I saved enough money to go to Russia.

Soon I was airborne with the other members of the commercial charter tour that would take us to Moscow for three weeks and Leningrad same. The entire prospect loomed before me seductive, enigmatic, enticing, but I hated the thought of going six weeks without getting high, and said as much to “Texas Jeannie,” a buxom Southern belle who’d taken the tour a year before.

“Don’t worry,” she drawled. “Them Ruskies got some of the best danged shit east of the Pecos, or west of it, depending how y’all see it.” Although I was slightly puzzled by her avowal of Russian high times, my fears were further allayed by an incident in Poland, where we stopped over to change planes and visit beloved Chopin’s birthplace. “Y’all oughta see what’s growing in the back yard,” said Jeannie. At first I took this to be an invitation of a perversely lubricious nature, but I caught on when we went in back of the great composer’s birthplace and found a patch of marijuana growing up stout and firm. From this moment forth my understanding of detente went through cartwheels or reconsideration.

On our second night in Moscow, I wandered the streets, and returned from sightseeing to find a note from Jeannie on my hotel door. When I got to her room, I found her and five other tourists sitting around on the floor, their heads obscured by a cloud of familiar-smelling smoke. At Jeannie’s welcome bidding, I fell to my knees and was handed a pipeful of dark green flakes of kaif, which smells like hashish but tasted like grass. It had come from the Caucasus Mountains in Georgia—just like Stalin—and it was just as powerful.

Jeannie had traded one of her many pair of blue jeans to a Russian head for the kaif we were smoking. She explained that the hunger of Russian youth for things American, like jeans, rock and jazz albums, psychedelic posters, and what have you, is so great that they’ll barter samovars, balalaikas, perhaps military secrets, and of course kaif in the most promiscuous fashion to get their hands on the trappings of decadent Amerikan youth culture. The realization that my old Moby Grape albums were the equivalent of cigarettes and stockings in a Saigon black market brought home to me the ineffable karmic value of never throwing away anything, no matter how faddy or ephemeral it may seem to jaded American hippies.

During my last week in Moscow, I was with some of my new Russian friends looking for a place to party. This is a great problem in Russia because of the acute housing shortage, which forces the Russians to live in rather close quarters. I was reminded of the familiar high school scene back home, where large parts of our youth are spent scouting locations to make out in.

Russians find it odd that Americans all have their own apartments, cars, food, cigarettes, orgasms: in the Soviet Union, these things are collectivized. Old and young must share their living rooms, their likes and dislikes, their cutlery and crockery, their vodka and ideologies, which are “monolithic” only in their mutual antagonism.

In short, the chances of our finding an orgy site seemed slim, when my friend Volodya struck up a conversation with a little man sporting a black goatee and heavy horn-rim glasses thick as stove lids. He turned out to be a sort of Russian bohemian, and in minutes had invited us to his apartment in a tottering old housing project. He told us we could use his little two-room “flet”, even his bed, while he socialized with us and shared our wine and kaif.

As it turned out, he fancied himself a painter and his apartment was crowded with awful day-glo canvasses of dogs pissing into space, lampposts shooting darts at children, and a picture of a man spreading his arsecheeks to reveal a peep at the infinite cosmos through his hole. Our host was one of those genuine Mad Russians you hear about. Twelve of us packed boisterously into the tiny place, puffing pipes of kaif and taking turns balling on the bed; the little man got wilder and wilder, drinking more than half of our wine. We played some of my rock albums—Hendrix and Pink Floyd—on his record player. I asked him if he had any examples of Russian rock music, and he replied, “You want to see example of Russian rock, da?” “Da,” I said. He went to a shelf and took down a paperjacketed album. He placed the record on the turntable, we listened for no more than a few seconds, and then he heaved the record out the window. “That’s Russian music,” he said.

“I knew Nicholas before he was a superstar,” he raved, reminiscing about his family. “My mother-in-law boy, is she fat! I took her to the Mayday parade and a C.I.A. Man offered to buy my missile secrets. . . . No, really, she’s very talented. She’s being sent to America on the cultural exchange program. In exchange, we’re getting Texas, Brooklyn, and Raquel Welch!” He began to roar out his life story, which became more and more horrible. Finally he dropped his trousers to show a long ugly scar left by Stalin’s torturers. At one point, I was bedding a young Muscovite honey when the Mad Russian ran in, brandishing a small scimitar. My friends dragged him away, and soon we left him sleeping on the floor, his snores and nightmarish outcries mingling with the laughter, sobs, arguments, and songs that poured into the common courtyard from every apartment. Somehow, the whole episode seemed to epitomize Moscow.

Leningrad is closer to the West than Moscow in more ways than one. During the centuries of Tsarist rule, the city reflected the Romanovs’ imitation of Western European culture. Even now that tradition persists. Walking down the Nevsky Prospect for the first time, I actually felt at ease among the younger, long-haired, more stylishly attired communists, some of whom were actually promenading in tie-dyed shirts.

The kids are hip and kaif is plentiful. With three young Komsomoltsy (members of the Lenin Youth Organization) I dropped in one evening to a local disco called the “Molotok” to hear the top local rock band. Their music, consisting of loud fancy guitar chords, lots of showy drum licks, and [an] almost funky bass line, was surprisingly together, and reminiscent of the high school bands that played in garages back home. On an impulse, I asked the drummer if I could sit in for one number. “Konyeshno!” he cried, smiling. The leader then announced that an American rock and roller was going to play, and that brought down the house.

I could barely hear myself through their applause and shouts. For the next several days I was followed around by several “groupskies” who believed I was a big rock star, and I did nothing to disillusion them.

Soon I met my first Russian dope dealer. His name was Misha, and he was as freaky as any Russian could hope to be. He was tall, swarthy, and bearded. He lived in his black market Levis and cowboy jacket. A signpainter by profession, he spent his time with foreign tourists and sold them dope, and had, in fact, served five years in a concentration camp for this activity. In a bastardized argot of hip Russian and Leningrad street slang, he invited us to his apartment to smoke some gashgish.

Gashgish is the people’s hash, imported from the Uzbekistan, a central Asian Soviet Republic near Afghanistan. He shared his apartment with a comely Lenin youth named Natasha. Our first time there, Misha emptied a papirosa (cigarette), and mixed the bitter Russian tobacco with some hash from a small leather pouch, then poured the mixture adroitly into the cigarette. I found it a bit harsh, but what the hell.

Later I gave Misha an American pipe and some screens and he was so impressed (and stoned) that he vowed never to smoke hash in cigarettes again, but Natasha swore, in her revisionist way, to go on smoking good Soviet papirosas. She did, however, take to “shotgunning” her reefers quite hungrily.

Misha’s scene was pretty loose, so one day I asked him what the neighbors thought.

“They think I am crazy,” he said. “And do you know, they are right? Every time they see me coming, the old one-leg and the ugly witch, they run into their rooms and slam the doors.” I regaled him with a few Florida redneck tales.

The last time I saw Misha, we got higher than Yuri Gagarin. Dostoeyevsky, that dark Russian, who once said, “consciousness is a disease,” would have been proud of us. Our minds met in cosmic detente, and Misha and I became increasingly mystic. A very Russian thing to be. I told him of my long-time dream of getting stoned with a genuine Russian. He told me about his dream of getting stoned with a real American.

“Est bog!” he cried excitedly, “there is a god!”

Source: https://hightimes.com/culture/from-the-archives-hash-in-the-u-s-s-r-1974/

Business

New Mexico cannabis operator fined, loses license for alleged BioTrack fraud

New Mexico regulators fined a cannabis operator nearly $300,000 and revoked its license after the company allegedly created fake reports in the state’s traceability software.

The New Mexico Cannabis Control Division (CCD) accused marijuana manufacturer and retailer Golden Roots of 11 violations, according to Albuquerque Business First.

Golden Roots operates the The Cannabis Revolution Dispensary.

The majority of the violations are related to the Albuquerque company’s improper use of BioTrack, which has been New Mexico’s track-and-trace vendor since 2015.

The CCD alleges Golden Roots reported marijuana production only two months after it had received its vertically integrated license, according to Albuquerque Business First.

Because cannabis takes longer than two months to be cultivated, the CCD was suspicious of the report.

After inspecting the company’s premises, the CCD alleged Golden Roots reported cultivation, transportation and sales in BioTrack but wasn’t able to provide officers who inspected the site evidence that the operator was cultivating cannabis.

In April, the CCD revoked Golden Roots’ license and issued a $10,000 fine, according to the news outlet.

The company requested a hearing, which the regulator scheduled for Sept. 1.

At the hearing, the CCD testified that the company’s dried-cannabis weights in BioTrack were suspicious because they didn’t seem to accurately reflect how much weight marijuana loses as it dries.

Company employees also poorly accounted for why they were making adjustments in the system of up to 24 pounds of cannabis, making comments such as “bad” or “mistake” in the software, Albuquerque Business First reported.

Golden Roots was fined $298,972.05 – the amount regulators allege the company made selling products that weren’t properly accounted for in BioTrack.

The CCD has been cracking down on cannabis operators accused of selling products procured from out-of-state or not grown legally:

- Regulators alleged in August that Albuquerque dispensary Sawmill Sweet Leaf sold out-of-state products and didn’t have a license for extraction.

- Paradise Exotics Distro lost its license in July after regulators alleged the company sold products made in California.

Golden Roots was the first alleged rulebreaker in New Mexico to be asked to pay a large fine.

Source: https://mjbizdaily.com/new-mexico-cannabis-operator-fined-loses-license-for-alleged-biotrack-fraud/

Business

Marijuana companies suing US attorney general in federal prohibition challenge

Four marijuana companies, including a multistate operator, have filed a lawsuit against U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland in which they allege the federal MJ prohibition under the Controlled Substances Act is no longer constitutional.

According to the complaint, filed Thursday in U.S. District Court in Massachusetts, retailer Canna Provisions, Treevit delivery service CEO Gyasi Sellers, cultivator Wiseacre Farm and MSO Verano Holdings Corp. are all harmed by “the federal government’s unconstitutional ban on cultivating, manufacturing, distributing, or possessing intrastate marijuana.”

Verano is headquartered in Chicago but has operations in Massachusetts; the other three operators are based in Massachusetts.

The lawsuit seeks a ruling that the “Controlled Substances Act is unconstitutional as applied to the intrastate cultivation, manufacture, possession, and distribution of marijuana pursuant to state law.”

The companies want the case to go before the U.S. Supreme Court.

They hired prominent law firm Boies Schiller Flexner to represent them.

The New York-based firm’s principal is David Boies, whose former clients include Microsoft, former presidential candidate Al Gore and Elizabeth Holmes’ disgraced startup Theranos.

Similar challenges to the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) have failed.

One such challenge led to a landmark Supreme Court decision in 2005.

In Gonzalez vs. Raich, the highest court in the United States ruled in a 6-3 decision that the commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution gave Congress the power to outlaw marijuana federally, even though state laws allow the cultivation and sale of cannabis.

In the 18 years since that ruling, 23 states and the District of Columbia have legalized adult-use marijuana and the federal government has allowed a multibillion-dollar cannabis industry to thrive.

Since both Congress and the U.S. Department of Justice, currently headed by Garland, have declined to intervene in state-licensed marijuana markets, the key facts that led to the Supreme Court’s 2005 ruling “no longer apply,” Boies said in a statement Thursday.

“The Supreme Court has since made clear that the federal government lacks the authority to regulate purely intrastate commerce,” Boies said.

“Moreover, the facts on which those precedents are based are no longer true.”

Verano President Darren Weiss said in a statement the company is “prepared to bring this case all the way to the Supreme Court in order to align federal law with how Congress has acted for years.”

While the Biden administration’s push to reschedule marijuana would help solve marijuana operators’ federal tax woes, neither rescheduling nor modest Congressional reforms such as the SAFER Banking Act “solve the fundamental issue,” Weiss added.

“The application of the CSA to lawful state-run cannabis business is an unconstitutional overreach on state sovereignty that has led to decades of harm, failed businesses, lost jobs, and unsafe working conditions.”

Business

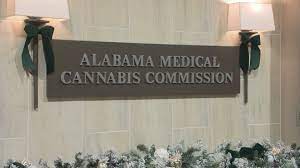

Alabama to make another attempt Dec. 1 to award medical cannabis licenses

Alabama regulators are targeting Dec. 1 to award the first batch of medical cannabis business licenses after the agency’s first two attempts were scrapped because of scoring errors and litigation.

The first licenses will be awarded to individual cultivators, delivery providers, processors, dispensaries and state testing labs, according to the Alabama Medical Cannabis Commission (AMCC).

Then, on Dec. 12, the AMCC will award licenses for vertically integrated operations, a designation set primarily for multistate operators.

Licenses are expected to be handed out 28 days after they have been awarded, so MMJ production could begin in early January, according to the Alabama Daily News.

That means MMJ products could be available for patients around early March, an AMCC spokesperson told the media outlet.

Regulators initially awarded 21 business licenses in June, only to void them after applicants alleged inconsistencies with how the applications were scored.

Then, in August, the state awarded 24 different licenses – 19 went to June recipients – only to reverse themselves again and scratch those licenses after spurned applicants filed lawsuits.

A state judge dismissed a lawsuit filed by Chicago-based MSO Verano Holdings Corp., but another lawsuit is pending.

Source: https://mjbizdaily.com/alabama-plans-to-award-medical-cannabis-licenses-dec-1/

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoPot Odor Does Not Justify Probable Cause for Vehicle Searches, Minnesota Court Affirms

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoNew Mexico cannabis operator fined, loses license for alleged BioTrack fraud

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoAlabama to make another attempt Dec. 1 to award medical cannabis licenses

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoWashington State Pays Out $9.4 Million in Refunds Relating to Drug Convictions

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoMarijuana companies suing US attorney general in federal prohibition challenge

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoLegal Marijuana Handed A Nothing Burger From NY State

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoCan Cannabis Help Seasonal Depression

-

Blogs2 years ago

Blogs2 years agoCannabis Art Is Flourishing On Etsy